About a month ago, German physicist Sabine Hossenfelder ran a YouTube video “Physicists Prove That Universe is not a Simulation.” As I understand the argument, they showed that if the universe were a simulation, it would have to obey the conclusions of Gödel’s Theorem, but that the real, observable universe doesn’t.

Dr. Hossenfelder wasn’t entirely convinced, and I’m certainly not qualified to judge, but check it out for yourself.

Then, just a few days ago, Mark McGrath and Ponch Rivera posted a No Way Out podcast, “Beyond the Linear OODA Loop: Jon Becker on Authentic Boyd Strategies,” where their guest maintains that we are living in a simulation. So what gives?

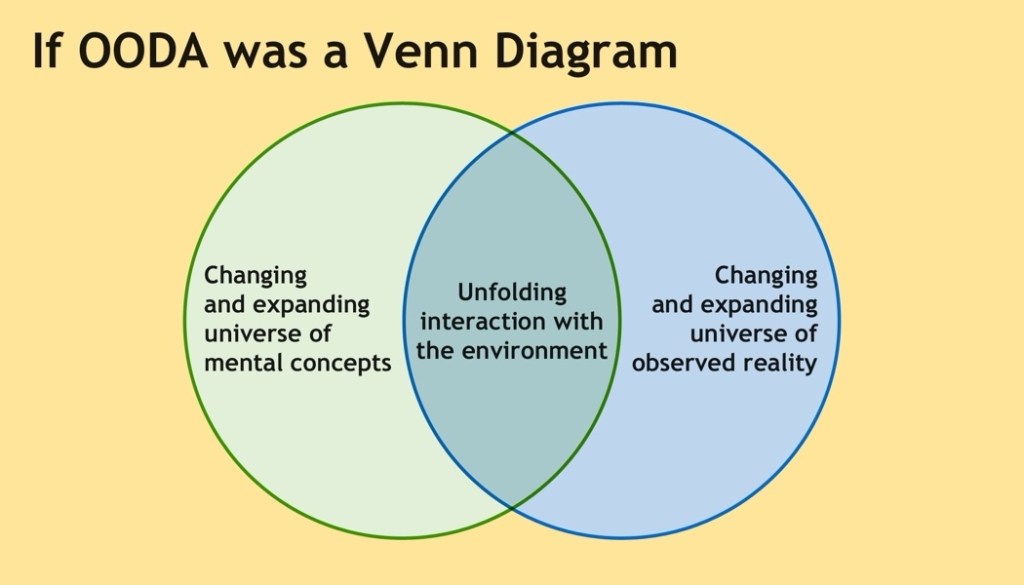

The difference is that Becker is not addressing the entire physical universe but is echoing John Boyd’s observation that:

To make these timely decisions implies that we must be able to form mental concepts of observed reality, as we perceive it, and be able to change these concepts as reality itself appears to change. The concepts can then be used as decision models for improving our capacity for independent action. “Destruction and Creation,” p. 2.

In other words, what we are living in is a simulated world generated by our mental models, and so our (simulated) world is indeed governed by Gödel’s Theorem. Becker, then, draws some interesting conclusions about how to live and operate in this environment.

Recognizing that we are living in a simulation, there are things we can do. We can not only mitigate the effects on ourselves by following Becker’s suggestions — e.g., recognize the effects of our egos, incorporate a range of perspectives (including those from the external environment), and always remember that orientation is a process and not a picture — but also exploit the fact that our impression of the unfolding situation is a simulation. We can do this in at least a couple of ways: internally to our organization as leadership and externally to it, as strategy. With John Boyd, everything is about mitigating and exploiting, with the latter providing the schwerpunkt.

Back in 2022, I did a presentation on the internal implications — that is, on leadership — of living in a simulation. After watching Jon’s podcast, I made a few updates to the notes accompanying that presentation. The fundamental conclusions, though, haven’t changed. For millennia, there have been people who recognized that what we regard as reality is actually a mental construct. Over the centuries, some of these folks evolved tools for manipulating this fact. So it stands to reason that leaders and strategists today could benefit from exploiting these tools. We refer to many of these as “magic.”

Think of them as the chi to the cheng you find in most management, leadership, and strategy tomes. Serious leadership gurus and strategists have dismissed them as tricks or “slight-of-hand.” Entertainment but good for little else. But the deeper question is, “Why do they work?” And why do they work even though you know the performer on stage is trying to fool you? It’s just like in a conflict: Your opponent knows you’re trying to deceive them. But you have to do it, anyway. If you look carefully, you’ll find that many of the most successful leaders down through history have found these techniques and made good use of them.

You can download the presentation here, and the notes, which I strongly recommend because I don’t think the presentation by itself will make a lot of sense, here. The Witch of Endor, by the way, makes her appearance on slide 53.

[The links in the paragraph above go to the versions that were current when this column was published in December 2025. Any more recent versions are posted on our Articles page.]

You must be logged in to post a comment.